Autumn 2006

Achievement Profile: Sonia Nieto

Steve Wolf

Life After TESL

Beloved ESL Teacher Mourned in Wichita

New Institute Hopes to Influence Language Policy

44th Annual Kansas CEC Conference

![]()

/Index/

/Letters/

/Profiles/

/Search/

/Podcasts/

![]()

Subscribe

for free!

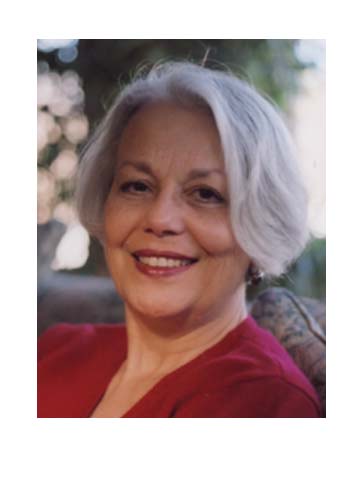

Sonia Nieto

Fighting for Students, Families, and Communities

1. How did you get into the field of ESL, bilingual education, and diversity leadership? Were there specific individuals, events, or experiences in your life which led you to this career?

Given my autobiography, I suppose I have always been in the field of ESL, bilingual, and diversity teaching and learning. As a child whose native language was Spanish and who was definitely born on “the other side of the tracks” (metaphorically speaking, of course, as the only tracks in Brooklyn were subway tracks and they were underground), from early on I heard – and was branded with – all the stereotypes and misconceptions about Puerto Ricans, native Spanish-speakers, and the poor. I decided to be a teacher when I was very young, perhaps feeling somewhere deep inside that teaching was one way to refute these images. I guess I thought even then that education and social justice were somehow intertwined.

I began my professional career in 1966 as a junior high school teacher in the Ocean-Hill/Brownsville community in Brooklyn, teaching English language arts, Spanish, French, and ESL. In fact, as an ESL teacher, I was labeled, right along with my students, as “NE” (non-English), although I have been perfectly fluent in English since shortly after beginning first grade. A couple of years later, in 1968, I was interviewed for a teaching position at P.S. 25, the first public bilingual school in the Northeast. P.S. 25 was in the forefront of the bilingual education movement. It was an exciting experiment, one that was to leave a deep imprint on my ideas of teaching and learning throughout my professional life. It was at P.S. 25, for example, that I learned that one could be academically successful and bilingual, and that being bicultural was an asset rather than a deficiency. I also learned the power of parent involvement and engagement. Several years later, as a doctoral student, these themes became the basis for my dissertation and they have remained significant interests of mine throughout my career.

2. What are you doing now? What are your current projects? What do you have on the backburner?

I was a teacher educator, researcher, and faculty member at the University of Massachusetts for 25 years, retiring in December 2006. It was a fulfilling and exhilarating career; I am so grateful to have been there and to have worked with wonderful colleagues and talented students. At the same time, I’m thrilled to be “retired,” meaning that I can now devote my time to writing, speaking, traveling, and many other projects. I am also editor of a book series for the Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishing Company. The series – Language, Culture, and Teaching – includes books with a critical edge that focus on literacy, second language acquisition/bilingual education/ESL, multicultural education, and related topics. I’m working on the fifth edition of Affirming Diversity with Patty Bode, my co-author for the edition. I’m also just beginning a new book that I’ve had on the back burner for a couple of years. The tentative title is Dear Paulo, and it will consist of letters from teachers to Paulo Freire. I’m very excited about it and want to get into it as soon as I can. So, as you can see, I’m very busy professionally and enjoying myself immensely. Other favorite projects including attending my granddaughter’s soccer games and hanging out with my other young grandchildren as well.

3. Which specific cultures and languages are you familiar with through direct interaction with learners from those backgrounds? How have these interactions added to your knowledge and awareness?

My most intimate interactions are, of course, with Puerto Ricans and other Latinos. But a long time ago, when I decided to focus my professional life on multicultural education, I made a commitment to learn about a broader range of people. Learning about people of different backgrounds is an energizing and enlightening experience, one that is sometimes uncomfortable because difference is not always easy. Nevertheless, it is always rewarding. As a result of this commitment, when I wrote the first edition of Affirming Diversity in 1992, I included case studies of youngsters not only of African American and Latino backgrounds – those who are usually included in work relating to multicultural education – but also students of Arab, Native American, Cape Verdean, Jewish, American Indian, and European American backgrounds. I heard from so many readers who were grateful that their backgrounds, so often missing in such accounts, were included in the text. In later editions, I’ve included students who are bicultural, adopted, and gay. It’s been an incredibly important learning experience every time that I’ve studied, and incorporated in my work, perspectives relating to different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

4. If you could give three pieces of advice to a person of any age who is considering a career in ESL, bilingual education, or multicultural education, what would you tell him or her?

First, know that you cannot ever know everything and, therefore, consider teaching a commitment to life-long learning. Second, rely on your students and their families and communities as your allies and a great source of support for your learning and your teaching. And third, develop close relationships with colleagues – whether in bilingual, ESL, or mainstream classes – so that teaching is not such a lonely endeavor.

5. What do you think are the most important challenges facing the multicultural education profession today?

The high-stakes standardized testing movement has created a climate in which multicultural education is often dismissed as irrelevant. Certainly, few matters related to diversity are included in either state standards or on the exams created to test students’ knowledge. As a result, many schools have concluded that diversity is not a legitimate perspective to include in curriculum, instruction, or school policies. Nothing could be further from the truth, of course, particularly at a time when our society is becoming more diverse than ever before in language, culture, race, and other differences. This means that advocating for multicultural education to be taken seriously is sometimes an uphill battle. It is, nevertheless, a battle worth fighting if all students are to be given an equal chance to learn.

Interview by Robb Scott

2006 ESL MiniConference Online

PDF conversion by PDF Online

Robb@ESLminiconf.net